|

|

I neglected making yearly resolutions last year, so I wanted to make them before I forget to do so this year. My first resolution is to learn to make grappa. It’s not that I like grappa that much, although I had some good grappa in Italy and some good chacha in Georgia. It is the learning process that I want to experience. This resolution will be my hardest for the year.

An easier resolution to accomplish is to bottle the 2014 second run wine that I made. When we pressed the must to put the 2014 in barrel, the wine was quite good just after fermentation. I decided to make a second run with with the pomace. 2014 may be a superb year for Napa grapes and we were excited about the 2014 Bordeaux-like blend that we have in barrel. It will also be interesting to see how these wonderful grapes do creating a second run wine.

Another resolution is to open the sealed underground qvevri and taste and bottle the wine. Although I made a qvevri wine at a winery in Georgia last year, this is my first attempt to make a qvevri wine here in the States. I sealed the qvevri in early November and am quite interested in how the wine will turn out. Depending on how warm or cold our winter will be, I’ll open the qvevri at the end of March or the middle of April. I have no idea of what I will get. For 2015 I also plan to make a qvevri wine. This time, I want to get the grapes into the qvevri earlier than I did last autumn. Last year, It was October before I started fermentation. I’d like to beat that by a month this year and have the grapes placed in the qvevri at the beginning of September. This resolution is also a challenge since we are not always home when the grapes are harvested.

At the end of the year, I’ll write how I did on this list of 2015 resolutions. Happy New Year and enjoy your winemaking.

Cheers,

Terry

I usually end the year reflecting on my New Year’s resolutions. However, we were so busy finishing our third book last New Year’s that I forgot to make winemaking resolutions for 2014. That didn’t stop us though. Kathy and I completed our seventh year of making wine. We started in 2008 when we determined that if we were going to write about wine, we should make wine.

Terry opening the Qvevri in Georgia. The new year, 2014, started with several wines aging. We had a buried qvevri of wine at Twins Wine Cellar in Napareuli, Kakheti, Georgia. Even though Georgia was over 6,000 miles away, we were still interested in how it was going to turn out. We found out in April, when on a Media FAM trip at the International Wine Tourism Conference in Tbilisi, our media group went to Twins Wine Cellar and Kathy and I opened our qvevri. The wine was a clear dark gold color. We received several comments from the media group such as the best qvevri wine they had tasted. This experience of making qvevri wine, prompted us to return to Maryland with a qvevri, bury it and make a qvevri wine at home. Qvevri winemaking is the only winemaking process that is on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Also at the beginning of the year we had a 2012 second run wine in carboys that should have been bottled during 2013. After finding space in the wine room, we bottled the two cases of this wine. There are pros and cons of making second run wines. I made it to learn how to make a second run wine and had low expectations on how it might turn out. My expectations were not even close to the way the wine turned out. The mostly Cabernet Sauvignon had an opaque dark purple color, with an aroma of black fruits. It was better than a daily table wine and I did serve it to guests. What I learned from the experience is that if you have a source of ultra-premium grapes, you can indeed make a pretty good second run wine. This prompted me to make another second run wine during 2014 with pomace from the 2014 wine we made with grapes from Stagecoach Vineyard in Napa Valley.

The best wine after the fermentation stage may be predictive of a vintage year. The third wine we had in barrel in January was at Tin Lizzie Wineworks in Maryland. This wine was bottled in August after spending 20 months in barrel. I would have liked to have kept it in barrel until October, but logistics of a custom crush facility came into play. The 2012 was a 100% Cabernet Sauvignon from Stagecoach Vineyard. Since we owned the two-year-old Taransuad French oak barrel, we decided to make another wine in it. We lucked out with 2014 being a fantastic year for Napa Valley grapes. We decided to make a blend of 75% Cabernet Sauvignon, 20% Merlot and 5% Petit Verdot.

The year 2014 was a rather full year of winemaking and bottling. We are anxious to see where we will head in 2015.

Cheers,

Terry

The Muscat grapes and juice have fermented. My last specific gravity reading was 0.996. There are some grape skins still huddled around the top of the qvevri. Since our weather was turning sharply cooler, I decided to seal and cover the qvevri for the winter. Using a solution of potassium metabisulphite sprayed onto a paper towel, I carefully wiped the top of the qvevri and the part from the top to where the grapes skins were resting. I also cleaned and sanitized the glass covering. Kathy rolled a coil of clay that she put around the circumference of the qvevri opening. We loosely fitted the glass and inserted a small strainer holding a burning sulphur tab. We let it burn for awhile and the removed it and pressed the glass into the clay. One of the benefits of using glass as a covering is that we were able to see through the glass and see the clay. We knew where we needed to press a little harder to form a seal.

During fermentation, I sealed the qvevri with plexiglass with an airlock. During aging, I seal the qvevri with glass. After the top was pressed into place, I poured about 2.7 cubic feet of play sand into the cavity. This covered the qvevri opening. After each bag of sand, I pressed the sand firmly. The qvevri top is several inches below the surface. Now we wait. I learned about patience in winemaking several years ago while making mead. It was cloudy and remained cloudy for several months. I read that it would take months and then it would clear up rather quickly. I waited and it did clear quickly about nine months later. I won’t have to wait that long to see what happens to the qvevri wine.

After each bag of sand, I pressed the sand down.

Our game plan is to open the qvevri in late March our early April. Our travel plans and the weather will have something to do with this. Between now and then, the wine and yeast, seeds and skins remain in the qvevri taking a long winter’s nap. If all goes correctly, when I open the qvevri the lees will have fallen first to the bottom of the qvevri. They will be covered by seeds and the the skins. The cloudy wine will have cleared. That is what happened to our qvevri wine we made in the country Georgia. While in Georgia, we did have wine from some qvevris that was still cloudy though. Unlike making wine in barrels or other winemaking vessels, I won’t be able to periodically test the wine in the buried qvevri. Perhaps this is where faith enters into the winemaking process.

Cheers,

Terry

Regardless of air temperatures falling to 37ºF (3ºC) the must and juice in the qvevri are happily fermenting. My original specific gravity reading on Saturday was 1.110. As of yesterday, the SG was 1.046. Put in terms of potential alcohol, when I started the fermentation there was a 15% alcohol potential. Now that is down to 7%. A little more than half of the sugar has been converted to alcohol despite the air temperature. Since the qvevri is buried under ground, the air temperature does not seem to bother it. Regardless of air temperatures falling to 37ºF (3ºC) the must and juice in the qvevri are happily fermenting. My original specific gravity reading on Saturday was 1.110. As of yesterday, the SG was 1.046. Put in terms of potential alcohol, when I started the fermentation there was a 15% alcohol potential. Now that is down to 7%. A little more than half of the sugar has been converted to alcohol despite the air temperature. Since the qvevri is buried under ground, the air temperature does not seem to bother it.

There is more of a cap now then when the ferment first began. However the punch down is quite easy. While in Georgia last fall, Kathy and I punched down the cap in a large 3,000 litre qvevri. It took considerable force to punch down the cap. With my small 23 litre qvevri, punching down is easy.

We seal the lid to the qvevri with a layer of clay. There is an airlock in the lid to allow a build up of gas to escape. Knowing that we could have temperatures below freezing soon, I placed Chacha in the airlock. It is not going to freeze.

Cheers,

Terry

We filled the press with the must. Our enthusiasm over making our first qvevri wine in the United States obscures the other wines that we are making with this years fruit. For the third time we are making wine at Tin Lizzie Wineworks in Clarksville, Maryland. We bottled the 2012 Stagecoach Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon in August. Our barrel was gassed and waited for us to fill it after 20 months of use. This year we decided to go with a blend of Bordeaux grapes: Cabernet Sauvignon 25%, Merlot 20% and Petite Verdot 5%.

Unfortunately the grapes arrived from Stagecoach Vineyard in the Atlas Peak AVA of Napa Valley while we were in Catalonia wine regions of Spain. The Tin Lizzie staff destemmed the grapes and started with the fermentation. I wanted to us D80 yeast since it is commonly used for all three grape varieties in our blend. Because of a broken bladder in the press, our wine was not pressed while we were still in Spain. We had an opportunity to press the wine on Saturday after a two-week fermentation.

The best wine after the fermentation stage may be predictive of a vintage year. We used stainless steel buckets to transfer the must from the fermentation bin to the press. While we were pressing, I tasted the free run wine. I was totally surprised. This was the best of the wines made at this point in the process. It was totally better than 2009s and 2012 after the fermentation. It could be bottled now and many people would like it. However, from the press the wine was racked into our barrel where it will age until August 2016. The Napa Valley harvest is producing some very flavorful grapes this year. The berries are smaller than previous years and more concentrated with flavors. When you decide to make wine, you have to make decisions prior to the harvest. The 2014 harvest may end up being one of the all-time greats in Napa Valley.

Our wine is in barrel; we’ll rack it off the gross lees in a day or so and then give it time to age. My brother commented that the winemakers in Napa that he visited last week want to use new French oak for each harvest. I am looking forward to our wine aging in a two-year-old Taransaud French oak barrel. The barrel has plenty of life and I am looking forward to a wine with less of an oak influence.

Cheers,

Terry

Sometimes plans do not work out. I had planned to purchase Viognier and make a Viognier wine in my qvevri. However, travel from mid-August through mid-October ruled that out. We were not home for stretched long enough to acquire grapes and ferment them in the qvevri. It is always a good idea to have a backup plan. Sometimes plans do not work out. I had planned to purchase Viognier and make a Viognier wine in my qvevri. However, travel from mid-August through mid-October ruled that out. We were not home for stretched long enough to acquire grapes and ferment them in the qvevri. It is always a good idea to have a backup plan.

We visited S&S Wine Grapes in Jessup, Maryland and purchased two 36 pound lugs of Muscat grapes from Lodi, Californis. This is late in the season for the grapes that had been kept in a refrigerated room for a month or so. We decided to destem them by hand casting the berries into one of three groups. The berries that would go into the qvevri would be placed in one group. They were very sweet and flavorful.

A second group contained berries that had turned color. We did not want them in the qvevri, we did press them and collected their juice. When tasted, the juice was still good. Our third group consisted of raisins. Those went onto a plate and set next to a southern facing window to get some sun exposure. The raisins also tasted good. They will be used in baking for the holidays.

The grapes collected from the berries to go into the qvevri measured at 25 degrees Brix. After filling the qvevri about ? full, I measured the specific gravity at 1.110. This was going to be a high alcohol wine somewhere near the 15% alcohol range. Then I made my first mistake. I pitched a yeast that I later discovered can only tolerate up to 13% alcohol. Since I did not want my wine to have any sweetness, I pitched another yeast that could tolerate high alcohol. Georgian qvevri winemakers use indigenous yeasts for fermentation. With 8,000 years of grape growing in Georgia, the yeasts have figured it out. I was not going to attempt to use the native yeasts on these grapes. The grapes collected from the berries to go into the qvevri measured at 25 degrees Brix. After filling the qvevri about ? full, I measured the specific gravity at 1.110. This was going to be a high alcohol wine somewhere near the 15% alcohol range. Then I made my first mistake. I pitched a yeast that I later discovered can only tolerate up to 13% alcohol. Since I did not want my wine to have any sweetness, I pitched another yeast that could tolerate high alcohol. Georgian qvevri winemakers use indigenous yeasts for fermentation. With 8,000 years of grape growing in Georgia, the yeasts have figured it out. I was not going to attempt to use the native yeasts on these grapes.

I covered the qvevri with a plexiglass lid that I drilled a hole for an air lock. There is sign of fermentation. Although the fermentation is somewhat slow. In part, it is cold outside and the forecast is for colder days and night time lows near freezing. The qvevri is underground so it should maintain a temperature high enough for fermentation to continue. After one day I did punch down twice; however, there was not a strong cap. I’ll continue to punch down and monitor the must in the qvevri and see how it is doing.

One last task was to run a coil of clay around the airlock where it fitted into the cover. We also ran a ring of clay around the outer edge of the qvevri so the lid would be pushed into the clay and form a seal. I’m interested to see how well this seal works.

Cheers,

Terry

I have been digging a hole for awhile. I had to place the qvevri in it several times to judge how much deeper to dig. Finally it was time to bury the qvevri. I placed the qvevri in the hole and tried to make it level. I slowly added soil, mostly clay-based around the bottom. The next task was to compact the soil. Oxygen can travel through soil. I recall reading that loose soil is up to 30% oxygen permeable whereas compacted soil is just 5% oxygen permeable.

Burring the qvevri and building the marani

I then added more soil and compacted it. I filled the hole to about two inches from the lip on the qvevri. The ground was leveled and then bricks were placed around the qvevri in a sunburst pattern. Now I can become creative as I start to make the marani. I added some sand between the bricks and then compacted it down. My next step was to add mortar between the bricks and add bricks around the perimeter. It needs some dry time. I hope my Georgian friends don’t laugh to much at my lack of my mason skills.

I’d like to add another layer of bricks over the bricks around the perimeter. Other than that, the qvevri is buried, and the marani has started. The next step is to make wine.

Cheers,

Terry

Previously I wrote about making a wire grid on my qvevri. The wire made applying the lime-based mortar quite easy. I simply mixed the mortar in small batches and started applying it to the outside of the qvevri. The wire seemed to help with applying the spreadable mortar that reminded me of spreading peanut butter on toast. I placed the qvevri in a wheelbarrow and applied mortar to half the qvevri on one day and the rest of the qvevri the next day. The thickness is just a bit thicker than the wire grid. I let the mortar dry for three weeks.

Coating the outside of the qvevri with a lime-based mortar. While in Georgia I asked about the purpose of the coating the outside of a qvevri. One winemaker commented that it helps protect the qvevri from tree roots. Another winemaker said their were earthquakes in the area and the coating will also provide protection from some ground shaking. What I am interested in is whether it will help slow down the rate of oxidation. Like wood barrels, oxygen can permeate the walls of the qvevri even when it is buried underground. I’d like to see the research that compares the amount of oxygen reaching the wine in a barrel as opposed to a qvevri.

The process was easier than I thought. I didn’t have a design, but I could see how some could put a design in the mortar. I did put Kathy’s and my initials and the year 2014 in the mortar near the top. I have no idea how many years the qvevri will be buried. My next task is to start working on the burial hole and marani.

Cheers,

Terry

On our first visit to qvevri maker Zaliko Bodjadze we learned that we should coat the outside of the qvevri with a lime-based mortar. Zaliko demonstrated a trick he uses to help make the mortar mix stay in place and adhere to the qvevri. I hope his method works. Zaliko used galvanized wire to create a grid on the qvevri.

Qvevri maker Zaliko Bodjadze demonstrates how he makes a grid out of wire before coating with mortar.

A quick trip to the hardware store to purchase some wire was followed by attaching the wire to the qvevri. I attached the bottom piece first although left some slack in the wire. I did the same for the top piece. I then began attaching the side pieces. I tightened the pieces. My next step is to coat the outside of the qvevri with a mortar mix.

The wire grid on our qvevri. Cheers,

Terry

While in the country Georgia, we learned about waxing a qvevri. The inside walls of a qvevri are coated with melted beeswax. This is often done by the qvevri maker after firing; however, winemakers can also wax the interior of the qvevri. I asked qvevri maker Zaliko Bodjadze, in Western Georgia near the village of Makatubani, at what temperature he applies the beeswax to the qvevri. Zaliko smiled and took his hand and touched a qvevri. He can tell the correct temperature by touch. Qvevri maker Remi Kbilashvili in Vardisubani, Kakheti in Eastern Georgia said he waits for the fired qvevri to cool to about 70ºC (158ºF) to apply the wax.

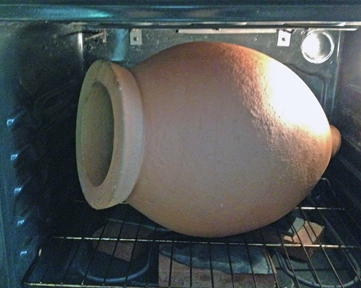

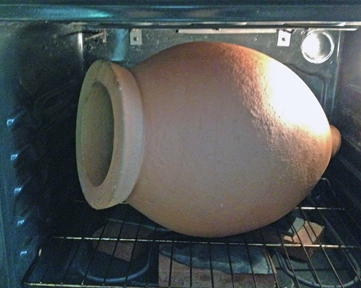

Winemakers that purchases qvevris that have not been waxed should heat the qvevri before waxing. They do this by building a fire in a pot and lowering into the qvevri to heat the inside. We decided that since our qvevri was small, to see if we could heat it in our oven. Making a few minor adjustments, we placed our qvevri into the oven and turned the oven on to 100ºF (38ºC). After a half hour we increased the temperature to 120ºF, then a half hour later to 140ºF and finally to 158ºF (70ºC). We left the qvevri in the oven at this temperature as we melted the beeswax.

Our qvevri was small enough to fit in our oven with a few modifications. We slowly heated the oven to 158ºF (70ºC) and kept the qvevri at that temperature for a couple of hours. We were told to melt the beeswax in a double broiler until it reaches a temperature between 230ºF to 248ºF (110ºC – 120ºC). It started to melt easily, but we could not get the temperature above 190ºF (88ºC). So we poured the wax directly into a pan and quickly heated it to 248ºF (120ºC). We took the qvevri out of the oven. I held the qvevri while Kathy used a paint brush to coat the interior with the hot beeswax. The paintbrush worked well and it looked like the walls of the qvevri were absorbing the beeswax. I began coating the inside walls as Kathy found a flashlight. It can be dark inside the qvevri and we wanted to make sure we did not miss any of the interior surface. We were finished in a few minutes. Kathy took the extra beeswax and poured it into a wine glass that she placed a wick into. Now we have a beeswax candle in a wine glass.

Melted beeswax approaching 230ºF to 248ºF (110ºC – 120ºC), At 230ºF the melted wax becomes translucent. Why did we wax the interior of the qvevri? New qvevris are highly porous and if not waxed, there is a chance that wine could leak out or water from the ground could seep in. By waxing the interior, the beeswax acts as a sealer for the porous walls.

We used a good quality beeswax. Kathy’s brother, Richard Linck, has an apiary in Marcellus, New York. The honey he collects is excellent and we made mead one year from his honey. We used beeswax from his bees to coat our qvevri.

Some of the qvevri interior is coated with beeswax that is pooling at the bottom of the qvevri. We used the beeswax in the bottom to coat the interior that we missed. The experience was fun. It was also humbling. We noted that for thousands of years, winemakers in Georgia have coated the insides of qvevris with beeswax. Being able to experience a part of ancient winemaking technology was a great learning opportunity.

Cheers,

Terry

|

|