|

|

Blushing Star Peaches In 2011, Kathy wanted to make a peach wine. We found a recipe to try from researching the Internet. This year we decided to once again make peach wine. During hot summers, a cold glass of peach wine with a frozen peach slice in the glass to keep the wine cool is a great afternoon drink.

This year we decided to pick our peaches. We picked 23 pounds of the white peach Blushing Star at Larriland Farm in Woodbine, Maryland. Blushing Star is a white peach with high acid. When we made our first peach wine six years ago, we used a combination of white and yellow peaches that were seconds. We picked extra peaches for pies and eating. We planned on using nine pounds for the wine.

Dicing the peaches Since the peaches were fresh off the tree, we had to wait a few days before cutting them up for making wine. We cut them in half and removed the pit. Then, using a spoon, removed some of the red pulp that was around the pit. We did this to avoid some of the bitterness that can come from this area. I then diced the peaches with the skins on.

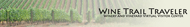

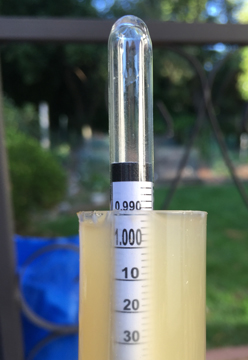

Since we were removing the pits and a bit of pulp, we measured ten pounds of peaches for the fermentation bin. To this we added three gallons of water. Two gallons were added at once. The other gallon was used to dissolve water. For example we placed 3 pounds of sugar in a sauce pan and added a quart about a third of a gallon of water. This sugar water solution was heated and stirred until the sugar was dissolved. Then it was removed from the heat and allowed to cool. After the first three pounds of sugar was added to the fermentation bin with the other water and peaches, the specific gravity reading was 1.045. After another three pounds of sugar, was added using the same method, the specific gravity reading was 1.076. We added another pound of sugar and raised the specific gravity to 1.083.

We used a total of seven pounds of sugar, a one-pound increase over the first time we made peach wine where we recorded a specific gravity reading of 1.084.

A few other items were added to the fermentation bin. Taking a cup of juice from the fermentation bin, we added:

¾ t of yeast energizer

3 ? t of acid blend

1 ? t of grape tannin

? t of pectic enzyme

? t and a pinch of potassium metabisulphite

Fermentation We actually have a measuring spoon for a pinch. After stirring the ingredients into the juice, we added the mixture to the fermentation bin. We waited until the next day to pitch the yeast.

This time, I decided to go with the Côte des Blancs yeast based on Internet research and the fact that I plan to back sweeten the wine prior to bottling. Kathy stirred the yeast in some of the juice and waited 20 minutes before pitching it into the fermentation bin. By evening, bubbles in the air-lock were noticed about every 20 minutes. By the next day, the bubbles were every two seconds. I’ll write another post next weekend with activity during the week.

Cheers,

Terry

On the second Sunday in April, Kathy and I racked our wine from its earthen qvevri. Our first task was to remove several cubic feet of sand covering the qvevri. The qvevri is buried below the ground level. When it was sealed in December, we filled the area with sand. Once removed, we inspected the clay seal between the glass top and the rim of the qvevri. The clay was still moist and still formed a seal around the qvevri’s opening. The glass covering did not come off easily. I had to twist it and then eventually I was able to lift a section. Working around the circumference, I was able to lift the covering. We cleaned the sand that was left surrounding the qvevri. We also removed the clay from around the rim.

After removing the sand, I broke the seal between the glass and the qvevri rim. The Vidal Blanc grapes were harvested on October 3, 2016 from Harvest Ridge Winery in Marydel, Delaware. Once harvested, we destemmed and crushed the grapes. The juice and many of the skins were placed in the 24-liter qvevri. Fermentation took a week. Once completed, a temporary covering with an airlock was placed over the qvevri opening. During the remainder of October and through November, malolactic fermentation took place. We replaced the temporary covering with a permanent covering in December by placing a coil of clay around the qvevri rim and pressing a piece of glass into the clay. Since we used glass, we could see through the glass and see the clay. There were no gaps. We then covered the qvevri and surrounding area with sand.

The wine near the opening of the qvevri was clear. Now in April, it was time to rack the wine to a carboy to settle. The first few inches of wine at the top of the qvevri was clear. Then we could see the skins. Of course we tasted the wine. The yellow colored wine had an aroma of flowers. The mouthfeel was velvety and reminded me of jammy yellow-stoned fruits. The wine had mild tannins. When we reached the grape skins, we transferred the skins and wine to a basket press. We had recently purchased an 18-liter basket press and this was its first use. About a gallon of free run wine was collected and added to the carboy. Adding light pressure to the press collected another half-gallon of wine.

After the first few inches of wine were racked into a carboy, the wine was cloudy. By the time we filled a couple carboys, our qvevri wine was cloudy with a lot of suspended particles. Two days later, the sediment was settling and the wine was clearing. Our plan is to rack again in May, then filter and bottle. Qvevri winemaking is an example of ancient winemaking. The egg-shaped qvevri remains buried in the ground. Some qvevris used to make wine in the country Georgia are several hundred years old. There are not many winemakers in the United States making qvevri wines. As far as we know, Kathy and I are the only people in Maryland making qvevri wine.

The wine from the press was cloudy. It will clear in a carboy for the next few weeks before filtering/ Many American wine consumers will need to be educated about qvevri white wines. Why did we ferment on the skins and macerate on the skins for a little over six months? One reason are the tannins. I always see tannins in a white wine as a gift. I like tannins. Another reason is more poetic. Georgian winemakers have told me that it is not natural for a child to be ripped from it mother at birth. Why would winemakers rip the white wine juice from it skins and seeds shortly after harvest?

Cheers,

Terry

In early October we had an offer to harvest Vidal grapes at Harvest Ridge Winery in Marydel, Delaware. Vidal was one of the white grape varieties that I had wanted to try in our qvevri. Previous vintages includes Muscat from Lodi and Rkatsiteli from Central Virginia. We did not harvest those grapes. Jason Hopwood, vineyard manager and assistant winemaker at Harvest Ridge let me know when the Vidal was ready to harvest. On October 3rd, Kathy and I drove the 90-minute trip to the Eastern Shore and had a wonderful time picking Vidal grapes in the vineyard.

Sorting while picking We sorted while harvesting. Kathy worked one side of a row while I worked the same row on the other side. Of course we tasted the grapes. They were sweet with floral tastes. Harvesting was also quite sticky. It did not take long to fill a couple containers and whisk them off to our home. This was a long day. By late afternoon we started to hand destem and gently crush the grapes. A couple hours later, we added 2.5 gallons of juice and two gallons of skins and seeds to the qvevri.

I reserved one cup of juice to pitch the yeast. I sprinkled one teaspoon of Aroma White yeast on top of the juice and waited 30 minutes. During that time I measured the specific gravity of the juice, 1.095. This potentially will make a wine with around 13% alcohol. I added the yeast to the qvevri and placed a temporary lid with an air lock over the opening. On the 4th of October I punched down three times. This was consistent for the next few days. By the 13th, fermentation was completed and the qvevri was sealed with the temporary lid.

Fermentation of Vidal in a qvevri By early December, I tasted the wine. It had a floral aroma, velvety mouthfeel with some hints of flowers and yellow stone fruit. After the tasting, I sealed the qvevri with a permanent glass top, one without an airlock. About eight inches of sand covered the qvevri. Then a marble slab covered the sand. I placed a tarp over the area. Our winter has mostly been mild through the middle of January. Although it has been below freezing for several days in a row, many more of the days had above average temperatures. We plan to uncover the qvevri and rack the wine in March or April depending on the weather.

Cheers,

Terry

Cabernet Franc panel I attended the Paso Robles Cab Collective “Cabs of Distinction” program at the Allegretto Vineyard Resort in Paso Robles. One session was about the other Cabernet focusing on Cabernet Franc. The panel included four winemakers and a moderator. Included on the panel were Bob Barth from Culinary Institute of America in Napa, Jeremy Weintraub, winemaker at Adelaide Cellars, Damian Grindley, winemaker at Brecon Estate, Anthony Riboli, winemaker at San Antonio Winery and Michael Mooney, winemaker at Chateau Margene.

During the panel discussion and tasting of the wines, major challenges to growing and making wine from Cabernet Franc were revealed. One challenge for this nobel grape that is a parent of Cabernet Sauvignon is that many consumers associate certain characteristics with Cabernet Franc. These traits include herbal and vegetative notes. Bob Barth was quick to point out that these characteristics are not associated with Cabernet Franc they are associated with underripe Cabernet Franc. These vegetative and herbal characteristics are caused by methoxy-pyrazine and to a certain degree can be reduced in the vineyard with certain practices. The winemakers on the panel made it known that they did not like these characteristics in underripe Cabernet Franc.

They are not alone. Living on the east coast, I’ve had the opportunity to taste many 100% Cabernet Francs that were easily very herbal and vegetative. The usual comment was that those traits was a common component of the grape. As a result, I did not use Cabernet Franc in a 2014 Bordeaux-style blend that Kathy and I have in barrel aging. I too do not like the pyrazine characteristics. I did taste one Cabernet Franc in souther Virginia that did not profile pyrazine characteristics, instead the most notable description was that of plums. So Cabernet Franc can achieve ripeness in some areas.

Wine tasting of Cabernet Francs The panel discussed the need for Cabernet Franc to be planted in the best vineyard plot, a need that would probably cause the vineyardist to pull out Cabernet Sauvignon. This is unlikely to happen. There is an economic impact and Cabernet Sauvignon brings in more revenue both from the vineyard and in the winery. Cabernet Sauvignon fetches a higher price and demand than Cabernet Franc. The economics of planting Cabernet Franc and making wine with it is another challenge for this nobel grape.

A third challenge was how to market Cabernet Franc. One of the panelists simply said he pours it in the tasting room. However it is easier to sell other wines than Cabernet Franc. There are a few people that like the grape and are asking for it. But this is a small group.

The audience asked about a comparison between Cabernet Franc grown in Napa and Paso Robles. The panel took a position that there are good Cabernet Francs grown in each area as well as Cabernet Francs with the herbal vegetative characteristics.

What are you feelings about growing or making wine with Cabernet Franc?

Cheers,

Terry

Early spring marks the time when a white wine made in a buried qvevri is opened. This week we opened our 2015 Rkatsiteli after macerating on the skins and a few stems for six months. For a bit of a recap. We sourced the grapes from a Virginia winery in September. Fermentation was robust overflowing the qvevri opening until I started punching down every three hours.

I placed a temporary lid with an airlock over the qvevri opening from October through December. At the end of December, I replaced the temporary lid with a glass lid without an airlock. Moist clay was used between the glass lid and the opening rim of the qvevri. Eight inches of sand covered the qvevri with a marble slab covering the sand. I used the marble to cover the sand so that no one or animals would step on or dig in the sand.

For three months the wine in the qvevri rested. During that time the seeds dropped to the bottom as did some of the skins. I was not entirely sure of what I would get upon opening the qvevri. In 2015, when Kathy and I opened the qvevri, the skins were at the top. I had to rack the wine to a carboy and let it settle for a few days, which it did very quickly. It seems that the wine in the qvevri was in a vortex all winter. This year there was a bit of a difference.

Some winemakers from the country Georgia suggested that I add stems to the must. The stems would help to cause the skins to settle and we should have a relatively clear wine at the top of the qvevri. In Georgian, Rkatsiteli means red stems, we put some of the redder colored stems into the qvevri when we filled it with grapes last September.

After removing the marble cover and scooping out a wheelbarrow-size load of sand, it was time to open the qvevri and discover this year’s wine’s birth. I noticed that the sand was quite wet, the further I dug to the surface of the qvevri opening. We asked our friend Nina K., who was born in the country Georgia, to open the qvevri. It took awhile to break the seal between the glass lid and the qvevri. The clay between the glass and the qvevri was still wet. It did not harden or crack during the last few months. After lifting the lid, we observed the wine in the qvevri. We could see the stems and skins; however, unlike last year, the skins were a few inches below a relatively clear yellow colored wine.

Marble covering over sand

Several inches of wet sand cover the qvevri.

Qvevri glass lid and clay attached to the qvevri Using a measuring cup, I scooped out some wine for a tasting. The Rkatsiteli was floral with hints of jammy yellow fruits. The mouthfeel was silky, everyone seemed to like that. The aftertaste had layers of floral and cooked jammy fruits. Actually, I was impressed with the wine and how it turned out in the qvevri. The next task was to rack the wine into a carboy. I do not have a press so I was only able to get three gallons of wine from the qvevri. We did take some of the pomace and let it drip for a night. We had enough liquid to make wine jelly.

Nina opening the qvevri

Kathy removing the clay, notice the wine over the skins in the qvevri

Tasting the qvevri wine I’ll let the wine in the carboy rest for a few days. It is already clearing with sediment falling to the bottom. My plans are to rack the wine from one carboy to another, then filter it before bottling. The ancient winemaking process of crafting wines in a qvevri is fascinating. It has been done for thousands of years and is the only winemaking process on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. We brought our 24-liter qvevri from Georgia. There is a qvevri maker in the United States who went to Georgia to learn from the few masters left. Billy Ray Mangham makes qvevris in Texas. You can learn about them and the qvevri winemaking that is being done in Texas at The Qvevri Project.

Cheers,

Terry

Cloudy wine and skins at the top of the qvevri while racking to a carboy, a 2015 winemaking resolution fulfilled. Sometimes making New Year’s resolutions is easy to do in January, but circumstances are fluid and may alter your hopes. That was certainly true with my 2015 winemaking resolutions. At best, I was one for three.

A year ago, my first resolution was to make grappa. This was based on travel for a family wedding. The wedding did not happen and I did not have an opportunity to make grappa. My second resolution for the year did not fare any better. I was suppose to bottle my second run wine. Call it being lazy or just not getting around to it, that wine is still in a carboy. Actually, that is the wine I’d like to turn into grappa.

I did accomplish my third resolution that dealt with qvevri winemaking. I did discover what my 2014 wine fermented and aged in a buried qvevri turned out like. There were a few surprises. The first is that the cap was still on the top and the wine under the cap was very cloudy. I racked the wine to a carboy and within a couple days it cleared. There was another racking and filtering before bottling the wine. I was worried about oxidation, but spending the winter in a vortex helped to deter oxidation with the dead yeast cells releasing carbon dioxide.

The second part of last year’s third resolution was to source Rkatsiteli grapes and make the wine in the qvevri. I also wanted to begin a month earlier than in 2014. I did accomplish this. I was able to get the grapes from a Virginia winery and had them going through primary fermentation a month earlier than the 2014 wine. Although I sealed the qvevri in November in 2014, in 2015 the qvevri was not sealed until the last day of the year. We had above average November and December temperatures, so I just let the temporary seal with an airlock in a lid suffice for the autumn months.

I’ll have to be a bit more realistic setting 2016 winemaking resolutions.

Cheers,

Terry

Sealed with a glass top, with a sample of the qvevri wine I waited to the last day of December to seal the qvevri and cover the area with several inches of sand. We had a very warm December with 29 of 31 days recording above average temperatures. Ten of those days, temperatures were in the 60s and 70s (15º -21º C). Previously, the qvevri was sealed with a plexiglass top with an airlock in the top.

Removing the temporary top I noticed a couple inches of wine over the cap. I decided to sample the wine. The wine had a yellow to gold color and was crystal clear. The aroma was very floral, reminding me of spring floral bouquets. There were floral hints on the taste, but most striking were the jammy yellow fruits including nectarines, peaches and yellow raisins. The wine was crisp with just a hint of tannins. I wouldn’t mind filtering and bottling now, but I want to follow the traditional Georgian protocol from the Kakheti wine region and leave it in the qvevri until March or April. It will be interesting to note the differences two to three months will have with the wine in the qvevri buried underground.

Qvevri covered under several inches of sand After placing a coil of clay around the opening of the qvevri, I sealed the qvevri with a permanent glass disk by pressing it down into the clay. Looking through the glass, I observed the clay pressing up against the glass. I made sure that the clay pressed against the glass around the circumference. Afterwards I covered it with several bags of sand. Then I placed a marble block over the opening. Just to be on the safe side, I covered the area with a tarp. The qvevri and wine will now rest for the winter. Depending on our weather, I will either open the qvevri at the end of March or beginning of April. Since I had the grapes in the qvevri a month earlier this year than in 2014, I may open the qvevri in March. That will allow the grapes and wine six months in the qvevri.

Winemaking

grape: Rkatsiteli

sourced from: Horton Vineyards, Virginia by way of Bluemont Vineyards

Primary fermentation: September 28th – October 8th

Qvevri sealed: December 31st.

Cheers,

Terry

The primary fermentation in the qvevri completed a few days ago. Yesterday I took the specific gravity reading and it measured below 1.000. After cleaning the qvevri’s lip and a few inches down with a paper towel and a bit of potassium metabisulfite, I sealed the qvevri with a ring of clay and a lid I made for the autumn months. For the winter months, I use a solid glass lid. For the autumn months, I use a plexiglass lid with a hole in the middle. In this hole I placed an airlock. I did taste the wine yesterday – very citrus and acidic. I’m hoping that natural malolactic fermentation will take place over the next few months to soften the acid. The primary fermentation in the qvevri completed a few days ago. Yesterday I took the specific gravity reading and it measured below 1.000. After cleaning the qvevri’s lip and a few inches down with a paper towel and a bit of potassium metabisulfite, I sealed the qvevri with a ring of clay and a lid I made for the autumn months. For the winter months, I use a solid glass lid. For the autumn months, I use a plexiglass lid with a hole in the middle. In this hole I placed an airlock. I did taste the wine yesterday – very citrus and acidic. I’m hoping that natural malolactic fermentation will take place over the next few months to soften the acid.

Challenges

This year’s fermentation went well. After dealing with the qvevri overflowing during fermentation, our next challenge was the area around the qvevri flooding. We had a multi-day nor’easter last week that caused run-off water to fill around the qvevri. I had to soak it up a few times. I did place tarps around and over the qvevri, but water still found its way in. The top of the qvevri is surrounded by bricks and mortar and is eight inches below the ground level. I did reset some on the ground level brickwork so that water would drain away from the qvevri. We had so much rain with the storm that if we get another like it, I expect that water around the qvevri will happen.

Another challenge was the low brix level of the grapes. At harvest the brix level measured 17º Brix and a hydrometer reading of 1.070. It is hard to second guess mother nature. A day after we received the grapes, it rained. Then it rained again. Then came the nor’easter. In retrospect, the vineyard manager made the right call, narrowly missing a tearful sky. I did chaptalize a bit raising the brix level to 20º Brix with a specific gravity reading of 1.080. I’ll be happy with a wine between 11% and 12% alcohol.

Future Plans

I’ll leave the wine in the qvevri alone for now. Prior to Thanksgiving, I’ll remove the present lid and replace the clay ring with new clay and place a solid glass lid on the qvevri. We will then fill the space above the qvevri with sand to ground level and the cover with soil and tarps. Depending on the weather next March, I’ll open the qvevri and rack the wine into a carboy to clarify for a few days. Last year the wine did not clarify in the qvevri but did clarify after I racked into a carboy. The vortex thing occurred in the qvevri and kept some of the smaller particles suspended in the wine. After a few days those particles settled and I was able to filter and bottle.

Cheers

Terry

Candle light and a barrel room provide a romantic setting. Some people associate wine and winemaking with romanticism. It is not difficult to imagine why a romantic vision is painted on people’s minds. Picture a candlelit barrel room. A small table with white linen has two red wine glasses with a dark ruby colored red wine. A single lit candle is on the table. Filled wine barrels surround the table and chairs for two. This is a romantic setting. However, winemaking is not very romantic especially at 3:00 AM.

When we first made a barrel of wine at Tin Lizzie Wineworks in Clarksville, Maryland we wanted to become fully involved with the day-to-day winemaking tasks. Our first activity at the winery was to get on our hands and knees and scrub the floor. Later, once the floor dried, we painted it. This was not at all romantic. However, we enjoyed being a part of the total winemaking experience. Someone has said that more time is spent extensively cleaning at a winery than in actually producing the wine.

More recently, I am fermenting Rkatsiteli grapes in a buried qvevri. I did use a commercial yeast. The fermentation took off and there was quite a bit of foam. The cap formed at the top of the qvevri and I had to punch down every three hours so that grapes and juice/wine would not spill out of the qvevri. That meant punching down at 12:00 AM, 3:00 AM and 6:00 AM as well as throughout the day. Getting up in the middle of the night to punch down the cap is not an example of a romantic setting. It was quiet and peaceful though, but not romantic.

I needed to punch down the cap every three hours. When it comes to winemaking, I spend most of my time cleaning and sanitizing. Another practice that is not romantic. The tool we use to punch the cap down has to be cleaned after a punchdown and sanitized before the next punchdown. Potassium metabisulfite, used to sanitize, is not romantic. Neither is washing and cleaning in the middle of the night. Then, using a paper towel sprayed with potassium metabisulfite, I wipe down the top lip of the qvevri.

There is no doubt that wine certainly has its place in romantic notions. Winemaking is not part of that romantic thought. At 3:00 AM, thought centers on getting the task finished and getting back to bed.

Cheers,

Terry

This morning the grapes rose to the top of the qvevri. Punch downs were every three hours. I wrote yesterday that we filled the qvevri to within two inches of the top or surface of the marani. Big mistake! In going to punch down early Saturday morning, I discovered that the fermentation was rather robust and juice and a few grapes escaped from the qvevri. Actually it was quite a bit of juice. The grapes had massed at the surface of the qvevri and after punching down, I had about four inches of space. We lost about 51/2 cups (1.3 liters) of juice. Minutes after punching down, the grapes rose up again gaining back two of the four inches after the punch down.

After punchdown. I should have known better. One of the Georgian winemakers commented that his grapes had overflown the qvevri during fermentation. A half hour after punching down, I had to punch down again since the grapes had risen to the surface of the qvevri. The next idea was to rack a litre of juice out of the qvevri and place in a small glass container with an air lock. We noticed that it was fermenting in the glass container. Once fermentation slows down, this will be returned to the qvevri.

Removing some of the juice helped. Initially the punch downs were five hours apart. That changed last evening. I had to punch down every three hours. Sunday morning arrived and I punched down at 3:00 am, 6:00 am and 9:00 am. At least I know it is fermenting and I am not loosing any more juice/wine.

Cheers,

Terry

|

|